Introduction

Hello! Welcome to my queer films blog. I am very excited to share my thoughts with everyone throughout the semester.

How to Survive a Plague: an emphasis on empathy and remembering

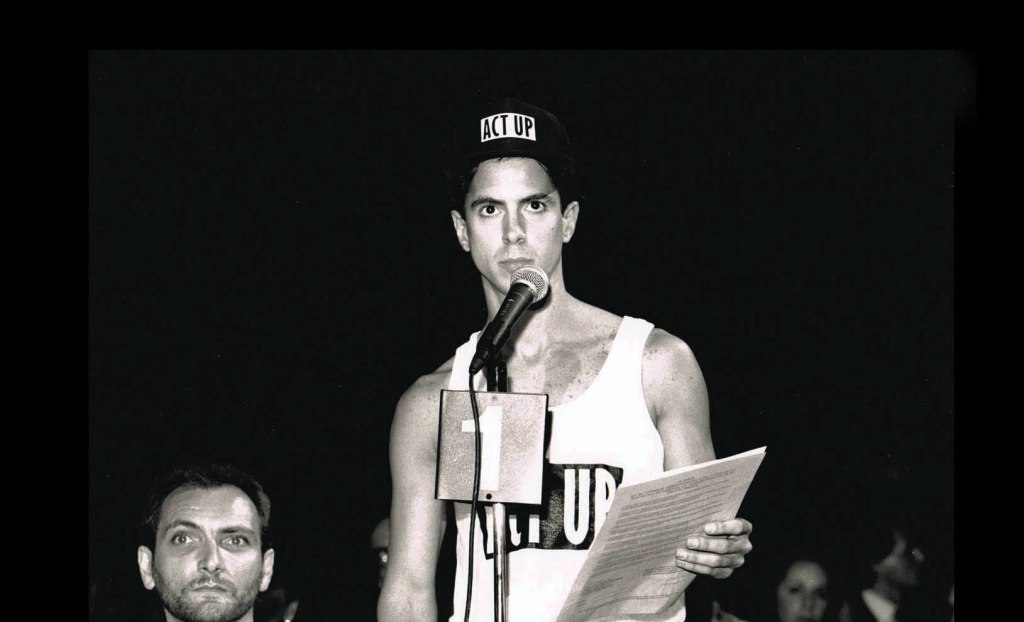

How to Survive a Plague is a wonderfully constructed documentary film about the AIDS epidemic. It follows the groups ACT UP and TAG, both groups who fought for action in the AIDS epidemic, and their activism within the movement. ACT UP stands for the “AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power,” and was created as a reaction to the United States government’s homophobia and neglect of the epidemic. TAG stands for “Treatment Action Group,” and was an independent research group that sought out better treatment for those who became victims of AIDS, and a cure for the disease. It is impossible to watch How to Survive a Plague without having an intense emotional reaction. As I sat and watched the film, I felt the anger and frustration of those whose voices were not being listened to, and the immense pain these people were in. This film does an outstanding job at highlighting the importance of empathy and remembering. The public attitude at the time was that the AIDS epidemic was unimportant because it was “just” queer people dying. There was a severe lack of empathy within the public reaction to the AIDS epidemic. Not only did the general public seem to not care, but the government was doing very little, if anything at all, to put an end to the quick spread of this disease. Thousands upon thousands of queer people were dying and ACT UP began to hold public demonstrations to bring attention to the issue. The AIDS epidemic was not only a public health emergency, but also a political and social issue as well. In this film, a member of the group ACT UP, Peter Staley, made an observation that has stuck with me since I watched the film. He essentially said that every day we as humans wake up and we make mistakes, which is a human thing to do, and that not practicing safe sex all the time is one of those things. He went on to say, “do not put people out to pasture and let them die because they have done a human thing.” All of the public demonstrations, interviews, etc, throughout this film helped the public form empathy for those who were victims of AIDS. While their protests and demonstrations were always peaceful and never violent, they did a fantastic job of displaying their anger and frustration; it is hard to watch the members speak and not empathize with the pain that they feel. They showed the public that they were not “just” queer people, but that they were people just the same as everyone else with jobs, children, loved ones, and hobbies.

In an interview Douglas Crimp claimed that ACT UP completely changed the way that the public discussed AIDS; it went from a conversation of blaming the victims to recognizing it as an actual public health emergency. Something spoken about in the interview was remembering, which I think is an important part of any event like this in history. What I found very interesting was him discussing the moralistic attitude towards sex that was created at this time. There was this thought that there was a good kind of sex and a bad kind, and that gay sex was something to be ashamed of. This is especially intriguing considering the way in which we are educated on the AIDS epidemic in school. For me personally, and many others I know, it was always a topic that was very briefly discussed in classes. Now that I have actually learned about the epidemic outside of high school, I am astonished that we essentially sweep this piece of history under the rug. We all know that historic events are important to remember so that we do not have to have the same discussions again in the future; we would never want the government to neglect a group of people in the same way again. Another key aspect of remembering this event is to promote safe sex. Still, in 2024, there is a lack of sex education for young people, and queer young people in particular. When we sweep these things under the rug and try to forget it because it was “just” queer people dying, we risk the lives of so many queer people yet again.

In a journal titled The politics of popular representation, Kenneth MacKinnon discusses the representation of AIDS in film, or lack thereof. When AIDS was mentioned in movies, it was only mentioned very briefly, or treated as a form of comedy and something to get a laugh out of. When it was found out that a celebrity had AIDS, it was often met with controversy and even criticism. An example of this is Rock Hudson. His entire life his sexuality was kept a secret and his management in Hollywood encouraged him to keep it that way. When the news of him having AIDS became public, it was a shock and was also only spoken about within the context of his sexuality. However, it did create a sense of public empathy since he was so widely known. It became less of a moral affliction when someone like Rock Hudson had it.